Hardware Abstraction Layer#

HAL is the abstraction layer between our high level logic and the hardware on the rover. It allows our code to not care about what hardware its actually running on, the specifics of communicating with ECE, or the design of the rover. The goal is to allow most of our code to work with high level commands that HAL will translate into low level instructions that ECE can understand.

For example: the person working on autonomy shouldn’t need to know the id of the light on the rover to indicate autonomous operation. Instead of having to write code to send the specific bytes of the instruction to turn on the desired LED to a specific port, he/she can just tell HAL “signal autonomous operation”.

Now let’s say URC has us use a different color light or ECE changes the location of the LED. With a HAL, we don’t have to go searching through the far reaches of the code base and into higher level (and somewhat unrelated) logic such as the autonomy nodes looking for references to functions/constants that need to be changed. All of this becomes abstracted behind HAL.

Communicating with HAL#

Communication is done via ROS’s actionlib library. I will not provide a detailed description of the library here, and going further will assume you have a basic working knowledge.

Each topic has a Goal, an Action, and a corresponding action server that handles messages sent to this topic.

An action encapsulates the return data while a goal encapsulates the data to send.

These classes are generated by catkin from .action files which should be in the actions folder in the relevant project directory.

The file name determines the name of the action and goal.

So if you had a file called MyFile.action, this would generated the classes MyFileGoal and MyFileAction.

Review the ros documentation for creating action files, but the general gist is as follows (the --- are required):

// Data to be part of the goal (what is sent to the action server)

int64 my_num

bool my_bool

---

// Data to be part of the action (what is sent back)

float32 flt

---

Each action server is a server that handles requests on a topic.

This is publisher-subscriber architecture where the action server is the subscriber and action clients are the publishers.

To send a request to HAL, you can use the Client class provided in actions.h in cmr_node like so…

cmr::Actions::Client<MyAction> ac(nodeHandle, topic);

// MyAction is the name of the catkin generated action class

if (!ac.isServerConnected() && !ac.waitForActionServerToStart(rosTimeoutSec)){

// Do some error processing

}

cmr::Actions::Result<MyAction> res;

cmr::Actions::Goal<MyAction> myGoal;

// set data to send to action server

myGoal.my_num = /*...*/;

myGoal.my_bool = /*...*/;

// send the request

if (!ac.call(goal, res, rosConnectTimeout, rosSendTimeout))

/*...*/

This will send an action on the specified topic which the action server in HAL is listening to.

Each command that HAL understands has its own action server. These commands can be sent from

any other node and the sending node does not depend on HAL itself because

actionlib provides a boundary to keep nodes separate.

actionlib can be used directly instead of using our Client class. The advantage of this would be to gain

more control over sending actions such as opting not to spin up a new thread to handle communication

with the action server. I’ll refer you to the actionlib documentation

for more information.

Some Relevant HAL messages#

Topic |

Goal |

Action |

Return |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

How it Works#

The insertion point for HAL is uart_hal_node.cc and mock_hal_node.cc.

The two nodes are interchanged based on the --mock parameter specified to the cmr script.

These nodes instantiate the respective subtypes of the abstract HalNode. HalNode is templated

on an ActionServerProvider. This is a policy that controls how new action nodes are created. The default

is to use a multithreaded policy and AsyncHal. The only way to change this is to manually change the

template parameter when the class is instantiated.

The ActionServerProvider provides functions such as addActionServer which is passed a (among other parameters)

a callable object to be the code that is run on receiving a request. This callable object is used to create an action server

which is encapsulated in a type-erasure object and added to a vector. This is because action servers have generic polymorphism

abstracting the argument goal and return action type.

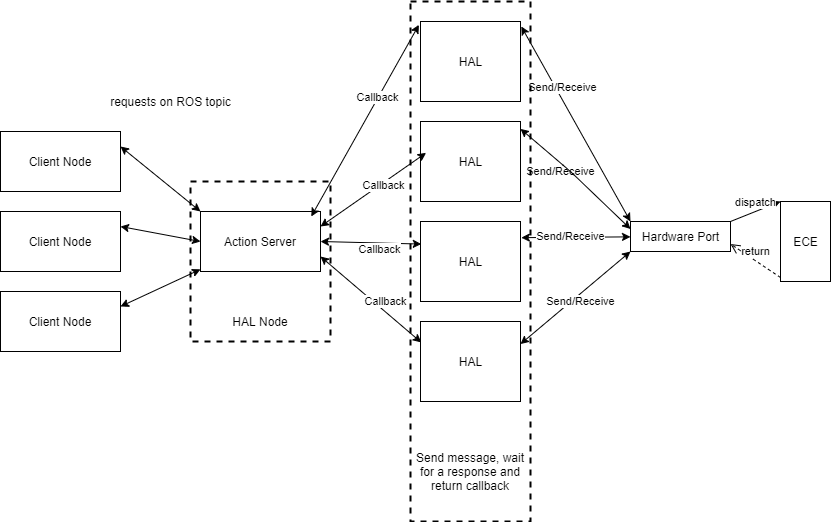

The multithreaded action server policy differs by running the callback code on a thread pool. Using this policy, once the action server receives the request from an external node, it pushes the user-supplied callback handler onto a thread-safe queue. A thread-pool will pop handlers off the queue in FIFO order, calling the code.

Callback handlers typically delegate requests to a concrete HAL type.

The HAL interface is thread-safe, and its functions are blocking.

Multiple threads can make concurrent requests to ECE via the higher level HAL command functions.

At the end of the day, there is only one rover and one hardware port which we can use. This port serves as a “choke point” for the multiple callback handlers occuring executing concurrently. Despite this, allowing requests to happen concurrently increasing throughput by allowing the hardware port to send large batches of messages at once and receive responses as they are sent back.

Here is a diagram displaying this control flow:

Let’s try an example of setting a LED. First, a client node sends a message on a ros topic such as set_led

with the message data corresponding to the ROS .action files.

The HAL Node in use has action servers that will detect these requests and enque a function onto a queue to be

picked up by threads in the thread pool. The task put on the queue utilizes the HAL interface

(by calling a function such as HAL::setLED()) and delegates the request to HAL.

Worker threads will pop these requests off the queue and execute them concurrently.

Thus, the HAL interface is accessed concurrently by multiple worker threads and these

are the functions that must wait for a response from ECE in order to determine the appropriate return value.

Based on the request, HAL will format the message and parameters into the correct message format and send them to

ECE via an FDPort. In async HAL, the FDPort is wrapped in a

thread safe decorator to synchronize access to the hardware port.

Once we get a reponse from ECE, the worker thread will be woken up and return the result

back to the action server, which will send it back to the client.

The Action server is not concurrent because it does a smal amount of work comparatively. It simply delegates requests and sends back the appropriate responses.

The control flow through non-async HAL is exactly the same, however action server callbacks are not executed in separate threads.

Interface#

The HAL interface originally used error codes, this has not changed to dovetail nicely with all the old code.

While I cannot speak for other HAL implementations, I can say that UartHal,

less the operations that are unimplemented, has the nothrow guaruntee.

For clients, this means that if a message has failed, you will get this status code in the status field of the

action that is returned to you (for most goals).

However actionlib has its own exception specification for the transportation of these actions and goals.

For UartHal, here are the meaning of the following status codes

0- success1- Bus connection errorFailed to read/write to board. This occurs when the underlying port read/write fails

2- Bus internal errorA non zero (failure) status code was returned by ECE

7- Board read failureAn error has occurred in parsing a response returned by the underlying port

For each status result, you can get a textual describtion with what()

Design Overview#

FDPort

util/port.h util/fd_port util/thread_port

ThreadPort is a decorator of FDPort,

it provides thread safe access by creating a separate worker thread.

This worker thread is the sole thread reading and writing the underlying FDPort.

Incoming writes to the FD port are put in a map keyed on the message id.

The message id is added to the data via the message formatter by HAL.

The ThreadPort assumes that no two message ids will be used at the same time.

When there’s enough data to send, or it has been long enough since the last flush,

the ThreadPort’s worker thread will send the queued data to the underlying port.

This worker thread also polls incoming data on the underlying port via the port’s

read_nonblock().

Using the message formatter instance passed to it on construction,

ThreadPort then reassembles the messages and sends it back to the thread who initiated the request by matching the

message id of the data read from ECE with the message id of the data written by CS.

ThreadPort maintains a thread_local stack of messages written.

On read, it will pop the last written message id off the stack and check if this id has been received.

If it has, it returns the data, if it hasn’t it blocks until the data becomes available or 30 seconds has passed,

whichever comes first.

If ThreadPort receives a message with an unparseable id,

it sets a failure on all unreceived pending messages.

Message ID

util/message_manager.h util/range.h

The new message format is discussed more deeply later.

Each message format has a message manager responsible for creating and inserting message IDS.

For the ascii format, the manager creates an id where the 3 MSBs (most significant bits)

are set based on a local counter that increments with each message.

The remaining 5 LSBS are assigned to each thread.

Thus, a single thread can send no more than 8 messages prior to reading, and a single HAL node can send messages

from no more than 32 different threads.

This is because the current format specifies a one byte ID.

The alternative option was to have the id simply increment at each message sent.

This behavior can be achieved quite simply by changing the idGenerator method in the factory function in port.cc.

The reason we chose to use the thread id for the message id is because currently,

there is never a time where a thread would ever write more than one message before reading.

Thus, this format prevents any possibility where all message ids were exhausted, and the same id is in use at the same time.

HAL

An FDPort is passed to it which it sends and receives messages on.

ThreadPort is a decorator for an FDPort,

and so the decorated FDPort can simply be passed to HAL.

It’s important to remember that when using the manual Hal constructor (the one in which a port is specified),

you wrap it in a ThreadPort if async operation will be used.

Hal is decoupled from the message format and the port used, along with any concurrency considerations.

Hal is thread safe if whatever port it uses is decorated with the ThreadPort.

To support the previous codebase, the old constructor is still there. The old constructor always creates a serial port, and always decorates that port with the ThreadPort decorator.

Hal contains the high level functions for communicating with ECE,

but shouldn’t be used directly unless you are working on the HalNode.

For general usage, see the Communication section.

Action Servers

node/actions.h node/action_server_provider.h node/thread_pool.h node/blocking_queue.h util/singleton.h

Actions servers are created and added to a vector of type erased action servers. Action Servers use ROS to receive and respond to requests on topics. They will then execute the callback specified, passing in the data received on the topic.

The async action servers do not execute this callback directly, but rather have a ThreadPool singleton that they

give these callbacks to.

The callbacks are enqued onto a thread safe non-parallel blocking queue.

Worker threads are notified when a new callback is added, pop the function off the queue and execute it.

Thus, the callbacks are executed in parallel.

By default, the amount of threads used is specified by std::thread::hardware_concurrency()

The threads of the action server will join on destruct.

Each action server listens on its own topic.

When a message is sent, the action server will handle the request.

Action servers are spun up by setupNodeFunctions()

Hal Node

Hal Node is now templated on an ActionServerProvider.

The ActionServerProvider is a policy that controls what type of action server are used.

Either parallel ones (action server callbacks executed on a thread pool) or synchronous (callbacks on same thread).

The Hal Node will use this policy to spin up action servers and specify their callbacks.

The main function of the Hal Node is to spin up action servers, using the specified policy, and set their callback handlers.

These callback handlers generally forward the passed data in the goal to a function in the HAL interface. The HalNode

is also responsible for instantiating the HAL instance that will be used by the action server callbacks. This is generally done via

YAML config files, but can also be done manually with the setHal function. The latter is primarily used for testing only.

Testing

MockEce

MockEce does what it sounds, it serves as an “endpoint” for a port to a memory buffer and simply returns simple responses in ECE format to valid requests from CS. This can do extra checking if you wish, but don’t forget about CheckerPort (see ASCII msgFormat) to keep things DRY.

To use, simply call mockResponse() passing in the fully formatted cs message to respond to.

This function can be used as an endpoint to the memory port callback via setOnWriteHandler().

Mock ECE parses the message passed to it, and creates valid responses for each type of message.

By default, MockECE just responds with successful acknowledgements of writes and 0s for data

for reads and queries but this can be changed using the setXXXResponse() functions.

These functions set the corresponding response data based on their name. Subsequent messages

parsed of the specified category will return the specified data instead of 0.

Truthfully, this could probably be implemented better with a GTest test fixture.

Tests

serial_port_test–> tests the nonblock read (and other capabilities) of the FDPort by using a pipe in memoryaction_server_test–> tests the multithreaded ActionServerProvider which is utilized by HalNode. Sets up an action server and connects to it via an action client. The client sends a bunch of messages and ensures a correct response. Roscore must be running, which is done automatically by the script start_master.sh which is a build dependency in cmake to the testmessaging_thread_test–> likeaction_server_testbut utilizes a Hal instance setup for testing. Also uses a CheckerPort to ensure correct messages are being sent. Once again, needs roscore running.thread_port_test–> tests the thread_port decorator

All tests can be run on any machine, they don’t need the Jetson, just ROS. To test on the Jetson, just switch the MemoryPort for a port to something else.

Message Format#

Each message format requires a formatter, manager, and id. These are polymorphic types; the formatter handles converting a series of objects into the correct format of bytes, the manager handles generating Ids, inserting them into formatted messages, and reading ids from formatted messages, and the polymorphic message id allows boolean equality testing and hashing of ids.

A message formatter’s constant interface should be thread safe. Concrete formatter types need to implement the private virtual format methods which are passed a byte vector of the binarized POD data that is being formatted.

The public interface of a message formatter allow formatting a series of any POD type. This is done by concatenating the sequence of POD types’ binary data (in big endian) into a single byte vector, and passing this vector to concrete subtypes via the NVI idiom. So for example: formatting the following:

formatWriteMsg(10, 'c', static_cast<long long>(-100));

Would concatenate the (typically) 4 byte representation of 10, 1 byte integral value of 'c',

and 8 byte long long representation of -100 into a 13 byte vector.

This vector is then passed to the concrete subtype which handles the specifics for how this data

is formatted into an ECE request.

These functions are templates that accept a parameter pack of POD types.

The output of these formatMsg calls lack an ID, which must be put in after the fact by the MsgManager.

In formatting the messages, the formatter should leave space for the id.

A MsgManager is responsible for computing an Id, and adding it to formatted messages. A callable object that returns

a subtype of a MsgId can be supplied to the MsgManager. This callable object is called each time

a message id is added to a formatted message with addMsgId.

Ascii Msg Format (Current Implementation)#

Max length: 32 bytes

CS → ECE

[Header][ID][OPCODE][SIZE][DATA]

Everything excluding the header is in ASCII hex.

For example, to send the one byte integer '5',

as the size this would be sent as two bytes 0x30 0x35 which are the characters '0' and '5' respectively.

- Header (1 byte)

‘R’, ‘W’, ‘Q’ depending on if the message is a Read, Write or a Query

- ID (2 bytes)

Internal use, message identifier in ASCII hex. Ex: ‘F’ ‘A’ ECE simply echo’s this back to us. It is simply so that we can keep track of who is sending what

- OPCODE (2 bytes)

The identifier for whatever you are reading/writing from/to. Internally, this is often referred to as the message id in the YAML files. I prefer to think of it as the opcode for the command. Once again this is in ASCII Hex

- SIZE (2 bytes)

Size of

[DATA]in ASCII hex. For a read this would be the size of the expected return data.

- DATA (Max 26 bytes)

For a read, this should be empty

- For a Query, this is further broken down into:

Sensor Address (2 bytes)

Expected response data size (2 bytes)

Remaining data (22 bytes max)

- For a Write, this is further broken down into:

Destination Address (2 bytes)

Remaining data (24 bytes max)

ECE → CS

[Start Delem][ID][STATUS][DATA][End Delem]

Delemiters:

Start is 1 byte: '$'

End is 2 bytes: NLCR ('\n' '\r')

- ID (2 bytes)

An echo of the ID we sent to ECE

- STATUS (2 bytes)

Status number in ASCII Hex. 0 indicates success. Anything else indicates a failure. If a failure occurs, the message can be thrown away.

- DATA (ASCII HEX)

The data to send back to us For Writes, this should just be empty

Example: The following are examples of the message format, and are not actual id’s or responses.

CS → ECE: "Q 0F 02 04 0B"

Spaces are not in the message, just shown to separate each part

ECE → CS: "$0F0A00000000\n\r"

CS Query (header 'Q') board status (opcode "02") of board with id 11 (data "0B").

Expect a 4 byte response (size "04") and has a message id of 15 (id "0F").

ECE Reply to message of id 15 ("0F") with a 4 byte inetger that is 0, and a status of 10 ("0A")

Usage

Use the makeMessageFormatter() factory function to create a message formatter.

This will also handle passing the message manager to the formatter.

To use, call the formatXXXMsg() function and pass in the arguments.

Arguments must be of the correct type.

So if you want a one byte sized integer,

cast the integer to a byte otherwise you will get a 4 byte sized integer.

For the ASCII message formatter, the first parameter is the opcode (also referred to as address)

for the message you are sending.

The remaining arguments are the data.

Do not manually pass in the header, id, or size of the data. This is all abstracted away.

Exceptions: Strong guarantee unless otherwise noted

Msg Formatter Design Overview#

The message format is implemented via a polymorphic MsgFormatter, MsgManager, and MessageId. When I made this I was really focusing on making the code ETC (easy to change). It seems likely that a format change will occur again and thus I wanted a system to be, well, easy to change.

Each concrete MsgFormatter has a concrete MsgManager and MessageId to go along with it. The MsgFormatter has functions to format a payload into read, write, and query messages. A user would simply only have to pass the types and positions of each data to the MsgFormatter, and the formatter will do the rest. A client would call the respective method of the MsgFormatter to format the type of message they aimed to send and pass the relevant payload data.

Each format function will bind to any number of any type of plain old data (POD) parameters (ie. integers, strings, booleans, vectors, or structs of PODs). This was done so that if parts of the message format change (such as the size of some part of the data, or a new piece of data is added) the only thing that would have to be modified is the call site of the format functions. This was done via parameter packs and templates. A downside of this however, is many calls of the format functions with diverse argument types can cause bloat in the executable size, however the positive is that details of a particular message format are extremely easy to change.

The MsgFormatter is responsible for taking raw payload data and converting it to the correct format,

adding headers or footers, and any metadata to go along with the message frame (such as size). Each

MsgFormatter is given a MsgManager when it is constructed.

The MsgManager is in charge of inserting message id’s into the message and also extracting the message id from

incoming messages from ECE. Finally, each MsgManager has a concrete MessageId that it inserts and reads from messages.

Each MessageId is hashable and comparable to any other MessageId via operator== and operator!=.

MessageIds can be used as keys in STL containers as well.

AsciiConversion

data_to_string.h

The Fmt static class contains the function convertToByteArray(), convertByteArrayToAsciiArray(), and

convertToAsciiByteArray().

convertToByteArray() functions take almost any arbitrary series of PODs

(plain old data) and convert it to a big endian vector of bytes.

As previously mentioned in the Usage section, the type of the arguments you use matter.

If you pass an int16_t you will get two bytes in the byte array regardless of if the actual value can

be represented with one. This allows small changes to be made really easy. Order of bytes change?

No problem just switch the arguments. Size of id changes? Easy, just change the type of the id

(actually, this is even easier as a new concrete MsgManager can added which has whatever id properties you need).

The downside of this is that in order to have proper generality and intuitive semantics,

there is admittedly a decent amount of copying being done. Eg. I don’t know if what’s being passed is

just a 1D vector of integers or a 5D matrix, either way the code works the same from the client’s perspective.

Move semantics helps greatly with this, but it doesn’t solve everything. Now I took the stance of

“Premature optimizations are the root of all evil” and will wait until a profiler says this is a bottleneck

(which will likely never happen). The only way to avoid this I thought of would be to make assumptions about the message format,

and thus make it harder to change.

convertByteArrayToAsciiArray() is very simple.

Just takes a vector of bytes and converts it to ascii hex.

convertToAsciiByteArray() just simply combines the two previous operations. Semantics are the same as convertToByteArray().

MsgFormatter

msg_formatter.h data_to_string.h

The MsgFormatter heirarchy uses the nvi idiom.

The base class will receive calls to its public interface,

convert the arguments to a byte vector via convertToByteArray() and pass that vector the the concrete formatter.

Thus, the semantics of the formatXXXMsg() functions are the same as convertToByteArray().

Data passed to these functions should be positioned exactly how you want the payload to be layed out.

The concrete formatter will then correctly format the data, inserting the size of the data and the

id based upon the message manager it is was supplied with. The formatter is created and the message manager is

supplied in the makeMsgFormatter factory method.

Calls to formatXXXMsg(...) will take the parameters and convert them into a big endian byte array.

For example, the short 500 will becomes the bytes 0x01 0xF4 with index 0 being 0x01 and index 1 being 0xF4.

Then this byte array will be handled by the concrete subtypes by calling the private virtual functions

corresponding to each format function.

Ex. To format a message with a write payload of [byte][int16][int64]

fmt->formatWriteMsg(theByte, theShort, theLong);

AsciiMsgFormatter

This class is the concrete subtype of MsgFormatter,

I’ll review some of the specifics relating to the ascii messaging format here.

Calls to formatXXXMsg(data) take the following transformations

The first paramater must be a byte and it must be the command opcode The msg formatter will prepend the correct starting delimeter ‘R’, ‘Q’, etc. It will leave 2 bytes of space after the delimeter for the message manager to insert ids (this is a 1 byte id, which is 2 bytes is ascii) It will convert the payload into ASCII hex For writes and queries, it will insert the size of the payload less the opcode after the opcode (byte 0 in the data argument) and before the rest of the data

MsgManager

msg_manager.h

This is passed to the msg formatter, and injects a formatted message with its id.

It controls how msgIds are calculated, and can pick out ids of formatted messages.

It also provides utility functions such as getting iterators to the start and end of a meessage in a buffer.

You can get the manager associated with a format with the getManager() function.

The MsgManager and MsgFormatter have parallel heirarchies. Thus, each formatter has its own manager.

Message ids are also polymorphic. They provide a simple interface which allows equality testing and hashing message ids.

It is good practice to make const member functions thread safe whenever possible, for the MsgManager this is an invariant

MessageId

msg_manager.h

The message id is hashable and comparable via != and ==.

It’s abstracted so that things about the message id (such as size) can be easy to change.

Yes there’s a cost of a vtable and dynamic_cast for something so simple,

but I doubt this is what you’re going to be concerned about for performance issues. std::hash<>

is also specialized so it can be used as a key in STL containers.

A wrapper MsgIdWrapper is also provided to give value semantics since MessageId is polymorphic and thus must be used

via a pointer to avoid splicing.

EceResponse

msg_formatter.h

This immutable struct groups the message data from ece. It contains the status number, decoded payload, and the msg id of the incoming message.

Testing

test/hal_test test/messaging_test

CheckerPort

CheckerPort is another FDPort decorator (see Async HAL).

To use it, you first “prime” it with the expectMsg() function.

Each time you call this function, the argument is compared to the data written to the port in the same order that

expectMsg() is called. After calling expectMsg(), Subsequent calls to write()

will check that what is being written is what is expected.

By this I mean it will compare the first message to the data passed to the first call of expectMsg().

Then it will do the same for the second call to write and argument passed in the second call of expectMsg().

If it’s not, an exception is thrown. The CheckerPort also has the didSeeAllExpected()

function which returns true if all expected messages have been sent to the port.

After checking the sent data (and throwing) if it does not match, the written data is then

delegated to the port that CheckerPort decorates.

The checker port will use the msg manager to ensure that the last id used by the MsgManager

is the same id as the message that is being written to the CheckerPort.

It also compares the expected data from expectMsg() with the unformattedMsg (see MsgManager).

That means that what should be passed to expectMsg() is not the message in its entirety but just the payload.

For the ASCII format specifically, this means that the expected message should not include the header character,

size, or message number.

Tests are implemented by switching the Port used by the UartHal to a

CheckerPort wrapped around a MemoryPort and just randomly calling functions in the UartHal interface a few throusand times each.

Format is also tested in an integration test suite with AsyncHal